Interestingly, respiratory stimuli (hypercapnia, hypoxemia, resistive loading) have minimal effect on arousal intensity ( 12) or the heart rate response ( 6, 19– 24). Little is known about the factors that modify the arousal intensity or magnitude of the cardiac autonomic response to arousal. More intense arousals are longer in duration ( 12), impair sleep resumption and sleep stability ( 13, 14), and are associated with greater surges in cardiorespiratory activity ( 5, 15) that may contribute to OSA pathogenesis ( 16– 18). Arousals also greatly vary in intensity, duration, and EEG morphology, and in their physiological consequences. The number of arousals per hour of sleep and the arousing stimulus are useful clinical measures of sleep quality. Frequent arousals and associated autonomic activation may also contribute to cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities that are a common feature of these sleep disorders ( 8– 11). Several chronic sleep disorders are characterized by excessive arousals and fragmented sleep and lead to daytime cognitive impairments, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), Cheyne–Stokes breathing, restless leg syndrome, and periodic limb movement disorder. Our work highlights the functional influence of episodic, involuntary airway defense reflexes on sleep and vigilance and cardiovascular function in healthy individuals. Our findings suggest that cortical feedback and tachycardia are integrated responses of the swallow motor program. Arousal duration and tachycardia increased in parallel as a function of swallow incidence. Critically, swallows were causally linked to the intense, prolonged cortical arousals and marked tachycardia. During sleep, swallows were overwhelmingly associated with arousal. Multiple swallows increase the magnitude of tachycardia via temporal summation, and blood pressure increases as a function of the degree of tachycardia. Tachycardia onset was temporally matched to glottic adduction-the first phase of swallow motor program.

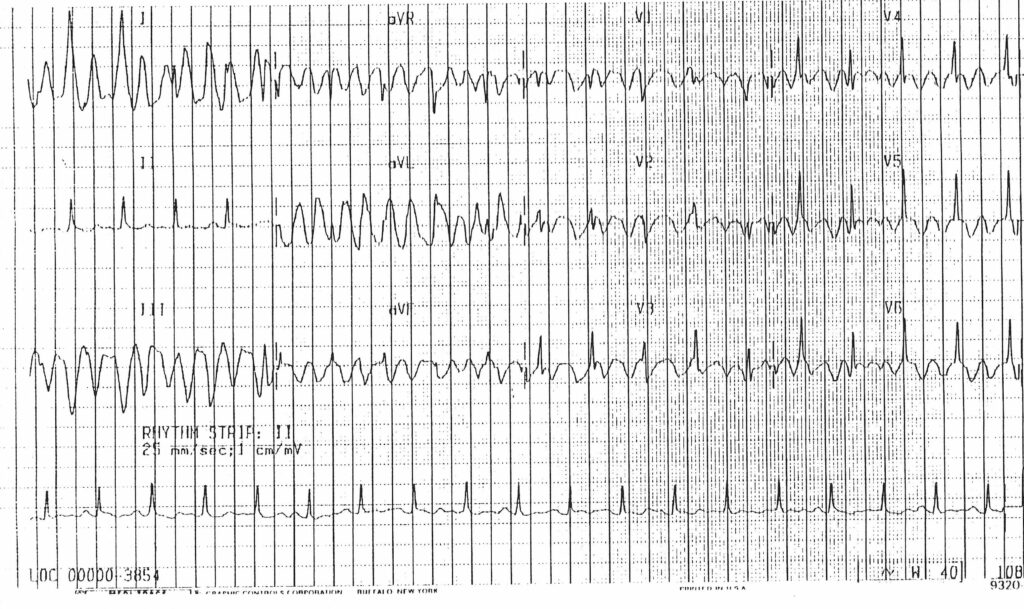

We found, in all subjects, that swallows trigger rapid, robust, and patterned tachycardia conserved across wake, sleep, and arousal states. In this study of healthy human adults, we examined whether reflex airway defense mechanisms, specifically swallowing or glottic adduction, influenced cardiac autonomic activity and cortical arousal from sleep. Yet factors that modify the arousal intensity and autonomic activity remain enigmatic. Sleep and arousability impact health acutely (daytime cognitive function) and long-term (cardiovascular outcomes). Arousals vary considerably in their frequency, intensity/duration, and physiological effects. People can discuss the risks and benefits of catheter ablation with a doctor.Cortical arousal from sleep is associated with autonomic activation and acute increases in heart rate. However, every procedure has complications, and people may still experience recurring tachycardia after catheter ablation. This procedure can help return the heart rate to normal. Ivabradine reduced the participants’ average daytime heart rate from 103 bpm to 84 bpm.Ī doctor may recommend more invasive forms of treatment, such as catheter ablation, for people with IST who do not respond to lifestyle changes or medication.Ĭatheter ablation delivers heat to the portions of heart tissue that cause rapid or irregular heartbeats. In a small clinical study, researchers gave people with ITS ivabradine twice a day for 6 months. Sometimes, a doctor may prescribe medications, such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or ivabradine, to reduce the heart rate and treat symptoms. Doctors refer to this as tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

Sinus tachycardia is usually a benign condition, but if it is persistent, it can lead to weakness of the heart over time. consuming less than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day.quitting smoking and avoiding other sources of nicotine.Treatments for sinus tachycardia may include: Treatments for sinus tachycardia vary depending on the underlying cause, but they usually involve a combination of lifestyle changes, medication, and, in very rare instances, surgery.ĭoctors address the underlying cause or condition when treating normal sinus tachycardia and do not often treat the tachycardia itself.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)